Poi Facts

The stigma surrounding poi has made it perhaps one of the most misunderstood of all foods. Luaus geared toward island visitors serve poi in tiny white paper cups as if to warn visiting poi virgins to “try it, but you probably won't like it.” A friend, visiting from New York, when encouraged to try poi for the first time, lightly licked the tip of the spoon, turned up her nose, and exclaimed, “I don't like it! It tastes like Elmer's glue!” I was taken aback, of course, and responded sharply and sarcastically, “oh, I didn't know you've eaten Elmer's glue!” Our naïve friends and relatives aren't the only ones putting down poi, some well-known folk have as well. Back in the 18th century, when Captain Cook stepped foot on the islands and tasted poi for the first time, he commented, “the only artificial dish we met with was a taro pudding, which, though a disagreeable mess from its sourness, was greedily devoured by the natives.” But more than 200 years later, Hawaii-born actress Kelly Preston advocated for poi on the David Letterman Show, proudly announcing her love for the purple paste and educating the show's viewers at the same time. But Preston's positive public poi proclamation is a rarity—most unenlightened people scrunch their noses when poi becomes the topic of conversation. Locals who grew up with the stuff and love it, like myself, learn to defend poi with a passion, taking it personally when someone unjustly criticizes it. It seems as if it is seen as the Rodney Dangerfield of the food world, getting virtually no respect. But the long history of poi confirms that this Hawaiian staff of life actually has a spotless reputation — and should more aptly be described as the Mother Teresa of foodstuffs. One can't think of a more benevolent, non-offensive food.

When the poi was on the table, people were not to argue or speak in anger. To the Hawaiian people, both before and after the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778, poi was a staple food, and a sacred one at that. Its significance is great in Hawaiian culture. In the journal of Polynesian Cultural History, Poi Making, by the Hawaiian historian Mary Kawena Pukui, the significance of poi is expressed: “Among my people, a child learned to pound poi at the age of eight, and it was the custom that each beginner ate every bit of the first batch he or she pounded. . . . My hair was coiled up and pinned securely so that there was no danger of getting a strand of it in the poi. We both turned out a smooth batch, which my aunt blessed (pule kahukahu) before we ate.” This sacredness is reflected in Hawaiian mythology where taro is believed to have the greatest life force of all foods. The god Wakea (sky father) and his daughter, Ho'ohokulani (child of Papa the earth mother), had a child named Haloanaka (quivering long stalk). The infant was stillborn and out of the spot he was buried, the first kalo plant grew. Haloanaka's younger brother, also named Haloa, became the ancestor of the people. In this way, taro was the older brother and man the younger—both being children of the same parents. Being first in birth, taro was considered superior to man himself.

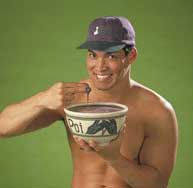

They baked or steamed the taro corm, or tuber, in underground ovens. The corm would then be mashed and mixed with water to make poi. The process has evolved over time. After the arrival of the white man, taro was boiled in pots over wood fires. After it was cooked, the children helped pull the outer skin off, cooling their fingers in water while they worked. Then the taro was peeled with sharpened opihi shells. Men then pounded the poi and it was stored while still quite firm, and water was added before serving.

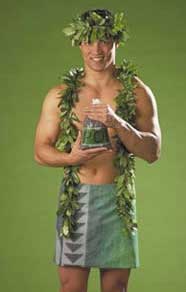

As the years went by, buying poi became more convenient to buy poi. Around 1948, poi became available in grocery stores thanks to the invention of the plastic bag. In 1955, poi became available in 8 oz. portion-sized cartons, similar to cottage cheese tubs. Today, poi even comes in handy 4 oz. squeeze tubes so you can have a shot of poi while sitting at your desk at the office or as a quick energy source on a long run.

In the early 1940s, there was a problem with substandard poi. Hawaii Governor Stainback solved the problem by establishing poi quality standards to control the problem of poi being excessively watered down. A full-time poi inspector was even hired at the time to maintain quality control. A city ordinance had condemned all poi with less than 30 percent solid matter as unfit for human consumption. Then there were the poi shortages, all a part of Hawaiian history. A poi shortage struck in 1946 and many Mormon families on O'ahu worked together and pitched in their spare time on nights and weekends to produce enough poi for their families. In 1992, Hurricane Iniki devastated taro crops on Kauai, where 2/3 of the state's taro supply is grown. More poi shortages are scattered throughout Hawaiian history due mainly to high demand and low supply during the summer party season when celebrations such as graduations abound. Labor shortages in the taro industry contribute to the problem, as well. In 1965, a State Taro Conference convened to discuss the taro industry. It brought together doctors, nutritionists and government officials and one of the topics discussed was poi as a baby and health food. A New York professor in attendance suggested poi as a substitute for infants and children with allergies to cereals. It was also suggested as a treatment for allergy-related conditions such as asthma, eczema, diarrhea and gastro-intestinal diseases. The New York professor also suggested a way to improve the marketability of the gray staple—by developing poi in other colors!

There's no doubt that poi is good for everyone. It's an excellent source of fiber and vitamins C and B-1, as well as potassium, magnesium and iron. And poi won't make you fat. It has fewer calories than rice (one cup of ready-to-eat poi has 120 calories; one cup of cooked rice has 250). Now is there anything bad anyone can say about poi? I think not. Songs have even been written about it, as poi has taken on a sort of whimsy in the entertainment world. Academy Award winning songwriter of “Sweet Leilani,” Harry Owens, recorded a song in 1940 which coined a phrase in local households. “Poi My Boy, Will Make A Man of You,” wasn't a big hit, but a tribute to the purple paste. It wasn't the only song featuring poi—Elvis sang about a fellow named Ito in “Blue Hawaii.” Bennett & Tepper wrote the lyrics of “Ito Eats,” “Ito is an eating boy, he never get enough from fish and poi.” If Ito only knew of the poi products of today, he wouldn't be able to get enough of any of them! Today, poi is used for more than just eating as a staple with fish or laulau. There's poi ice cream, poi English muffins, poi bagels, poi cookies, kiwi-flavored poi, poi cheesecake, and even poi dog biscuits for your poi dog. The possibilities with poi are endless since poi is such an adaptable food.

So the next time someone asks you, “what's there to know about poi?” Tell them that the future of poi is as exciting as its past … and that's pretty exciting. Copyright 1998-2009 by Craig W Walsh

|